Cassey Lee

ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute

Introduction

Southeast Asian countries have experienced tremendous growth in the past decade. The stellar performance of some of these economies have been accompanied and made possible by structural change. This has involved changes in the shares of the three broad sectors of the economy, namely agriculture, manufacturing, and services. These bring about new economic challenges that often make it difficult to sustain growth in the future.

As Southeast Asian countries are not homogenous, the economic challenges of structural transformation vary across the region. Despite the rapid growth experienced by many countries in the region, significant variations in the levels of income per capita remain. Recent theoretical and empirical research (primarily based on developed country experiences) provides some insights on how structural change can be studied in Southeast Asia. The existing body of research literature provides policymakers with a broader framework that can be used to make sense of the long-term trajectory of their economies.

The goal of this essay is to provide a brief and comparative analysis of structural change in Southeast Asian countries since the 1960s. It also explores some of the economic challenges that confront these countries in achieving robust and sustainable growth—given their current economic structure and within the global trade environment. The economic heterogeneity across countries in the region raises interesting questions about income convergence and regional integration.

The following section provides a broad review of the literature on structural change, followed by a discussion on the pattern of structural change in Southeast Asian countries. Next, the article focuses on changes in manufactured exports before turning to an analysis of the role of consumption and, finally, the conclusion.

The Literature on Structural Change

The term “economic structure” often refers to the composition of an economy in terms of different types of activities or sectors, generally, agriculture, industry (manufacturing and mining), and services. Structural change or structural transformation, then, concerns the reallocation of economic activity across these broad sectors (Herrendorf et al. 2014).

Historically, countries undergo two phases of structural change during the development process. In the first phase, countries undergoing industrialisation experience a shift in the relative importance of economic activities (in terms of output and employment) from agriculture to manufacturing (Syrquin 1988). In the second phase, often labelled as deindustrialisation, the relative share of manufacturing declines while that of services increases.

The process of structural change is however more complex than mere changes in relative shares of agriculture, manufacturing, and services. Potent dimensions of change which signify this complexity include demand, technology, employment, factor accumulation, migration, location, demography, income distribution, and the environment.

To be sure, the theories and empirics of structural change tend to focus on a number of drivers. From a domestic demand perspective, a rise in per capita real income is accompanied by a decline in the share of food in final demand and an increase in producer goods, machinery, and social overhead (Chenery and Syrquin 1986). Not only is there an increase in the production of manufactured goods with greater income elasticity, but a higher proportion of these goods are intermediate goods—indicating greater inter-sectoral interactions and dependencies. These are also known as income effects associated with the Engel curve (Comin et al. 2021). Sectoral change is also driven by changes in the prices of manufactured goods relative to agricultural goods (price effects)—which is brought about by differences in productivity growth. From the supply side, structural change is driven by sectoral differences in rates of productivity and technological growth and capital intensities (Comin et al. 2021). Even though much of recent empirical work has focused on the demand-side, technological change and capital accumulation are not alternative explanations but instead are parallel processes that drive reallocation of resources across sectors. Thus, recent empirical work has also emphasised the importance within country of sectoral differences in technical progress (Herrendorf et al. 2015) and country-specific technological factors (Eberhardt and Teal 2013).

Trade also affects structural change. This is particularly significant for small economies. In this respect, the rise in the trade of manufactured goods is another characteristic of industrialisation in many countries (Syrquin 1988; Syrquin and Chenery 1989). Uy et al. (2013) argue that trade affects structural change through three channels. First, decline in trade cost affects specialisation which brings about sectoral reallocation of labour. Second, sectoral productivity differences also induce reallocation of labour. Finally, trade induces rapid growth which amplifies the income effects on demand. The amplification of demand effects via trade is also emphasised by Matsuyama (2019).

In empirical studies, one finds two approaches to the measurement of structural change. The first focuses on the production side, and in such cases, measures used include employment shares and value-added shares in the gross domestic product (GDP). The second concentrates on the consumption side. This can be measured in terms of final consumption expenditure’s share of GDP. In the next section, these measures are used to assess structural change in Southeast Asian countries.

Growth and Structural Change in Southeast Asia

Growth trajectories

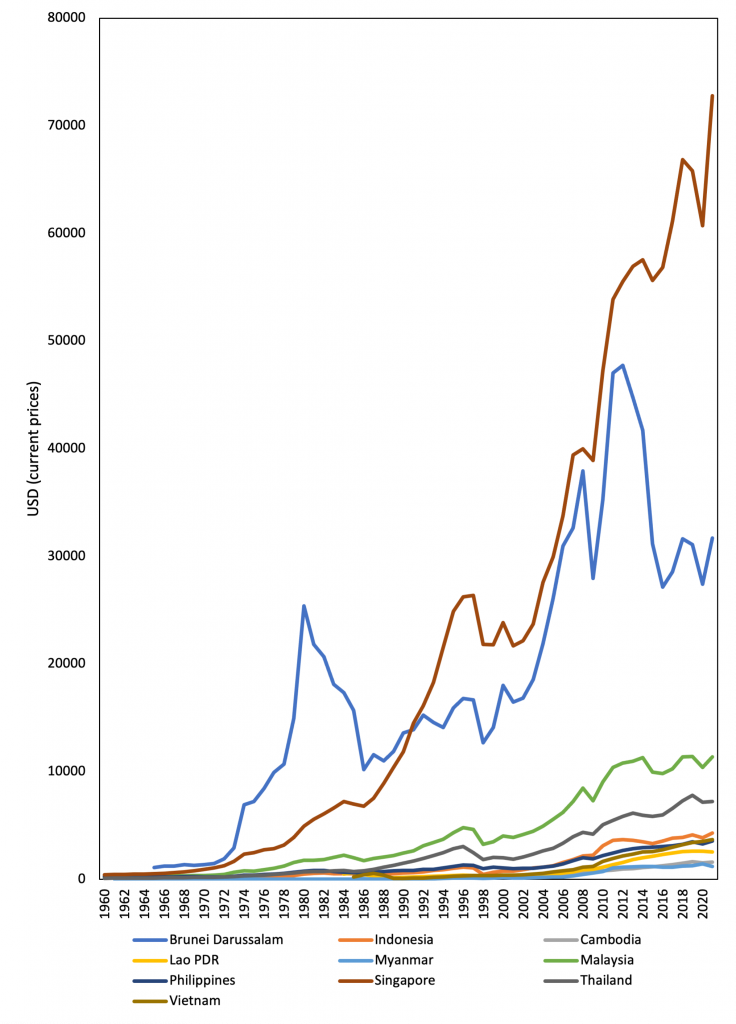

Differences in growth performance since the 1970s have brought about significant heterogeneity in income per capita across countries in Southeast Asia (Figure 1). Brunei Darussalam and Singapore are on the higher end of the income per capita spectrum. Next, in the upper middle-income level are Malaysia and Thailand. Clustered below that are the middle-income countries—Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Lao PDR. The two least developed countries in the region are Cambodia and Myanmar.

The country with the highest per capita income, Singapore, managed sustained high growth for almost 30 years (1970–2000) (see Table 1). Brunei is an outlier in this aspect, being heavily dependent on oil production/export. Both Malaysia and Thailand experienced rapid growth for a slightly shorter period of about 25 years (1970–1995). Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam (CLMV), in turn, picked up their growth rates in the decade from 1995 to 2005 but they failed to sustain their high growth rates in the period 2005–2010, with the exception of Vietnam. There were signs of resumption in rapid growth rate in these countries (except for Myanmar) from 2015 to 2019 but by all accounts, this would have been terminated by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021.

Figure 1: GDP per capita (nominal).

Source: World Bank.1

Table 1: Average output growth rate, 1970–2019

| 1970–1975 | 1975–1980 | 1980–1985 | 1985–1990 | 1990–1995 | 1995–2000 | 2000–2005 | 2005–2010 | 2010–2015 | 2015–2019 | |

| Brunei | 3.8 | 11.5 | –4.2 | –1.6 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.9 |

| Indonesia | 8.3 | 7.8 | 4.7 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 0.7 | 4.5 | 5.4 | 5.3 | 4.8 |

| Lao PDR | 2.7 | 0 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 4.8 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 2.7 | 6.3 |

| Cambodia | –4.6 | –6.1 | 0.5 | 6.9 | 4.5 | 7.7 | 9.2 | 5.9 | 4.2 | 7.3 |

| Myanmar | 2.5 | 7.8 | 4.3 | –0.1 | 3.3 | 7.2 | 5.6 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 4.5 |

| Malaysia | 7.6 | 7.9 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 9.3 | 4.8 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 4.2 |

| Philippines | 6.1 | 5.5 | –0.6 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.7 | 6.6 |

| Singapore | 8.8 | 8.0 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 8.4 | 6.2 | 4.9 | 7.2 | 4.7 | 3.7 |

| Thailand | 5.5 | 7.4 | 5.3 | 9.8 | 8.1 | 0.7 | 5.3 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 3.6 |

| Vietnam | 3.7 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 6.4 |

Source: Asian Productivity Organization.1

Structural change – Industrialisation and (premature) deindustrialisation

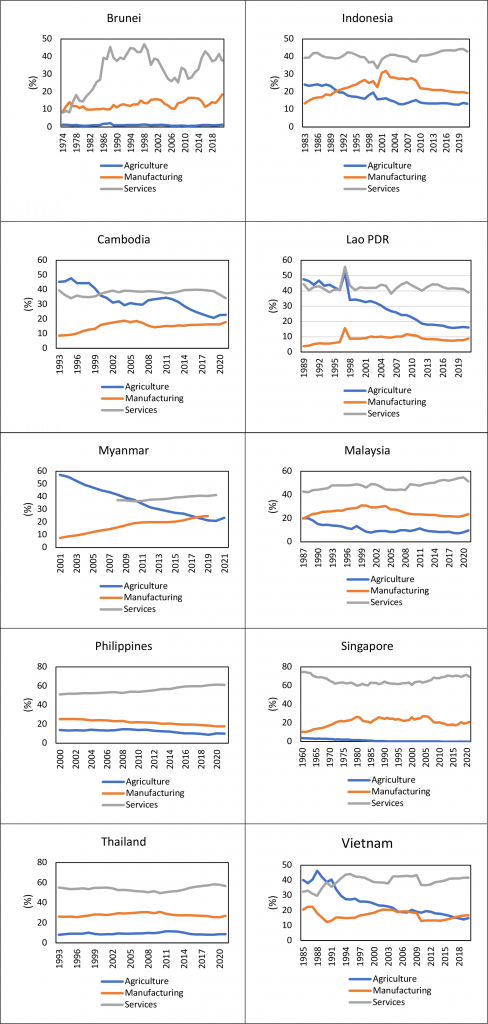

The reallocation of resources across and within sectors underpins economic growth. The question to ask, then, is, how has the structure of Southeast Asian economies changed over time during the different phases of economic growth and slowdown? Distinct patterns of structural change can be noted for different sets of countries.

Countries in the middle-income and higher income categories such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand exhibit a hump-shaped curve for the manufacturing share of GDP (Figure 2). However, the inflection point which marks the onset of decline in manufacturing share of GDP—often regarded as deindustrialisation—varies across countries: Indonesia (peaking at 32% in 2002), Malaysia (31%, 2000), Singapore (27%, 2006), and Thailand (31%, 2010). The services sector in these economies is seen to have contributed a substantial share of the GDP when it reached between 50% to 60%. In the case of Singapore, the transition to lower the GDP share of manufacturing is a bit unusual—this stagnated at around 23%–24% for 25 years between 1980 and 2005, before declining.

Amongst the CLMV countries, the GDP shares of manufacturing and services in both Cambodia and Lao PDR stagnated below 20% and 10%, respectively. In short, industrialisation appears to have stagnated in these countries. In the case of Myanmar, its manufacturing sector was making good progress, at least until before the military coup in 2021. Vietnam’s manufacturing sector, in turn, has been making steady progress especially since 2010. The GDP share of the country’s manufacturing and services sectors in 2019 (at around 17% and 41%, respectively) do suggest that there is significant room for further industrialisation.

Figure 2: Sectoral composition of GDP.

Source: World Bank and CEIC.1, 2

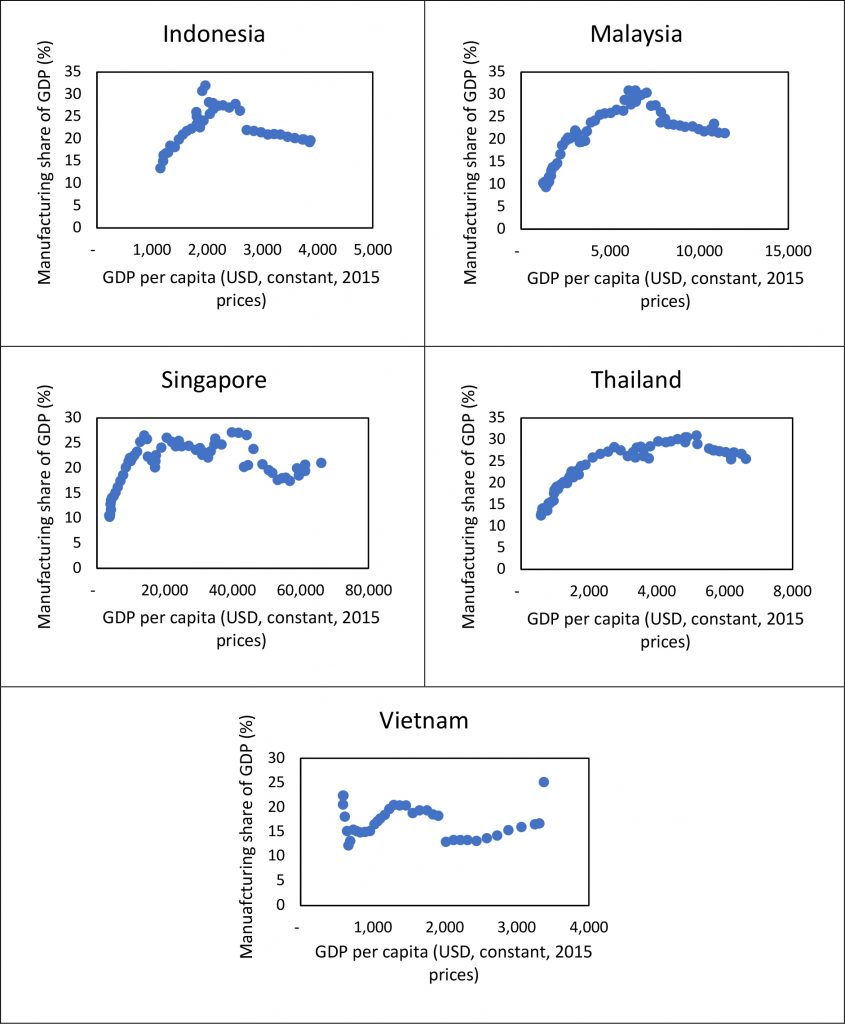

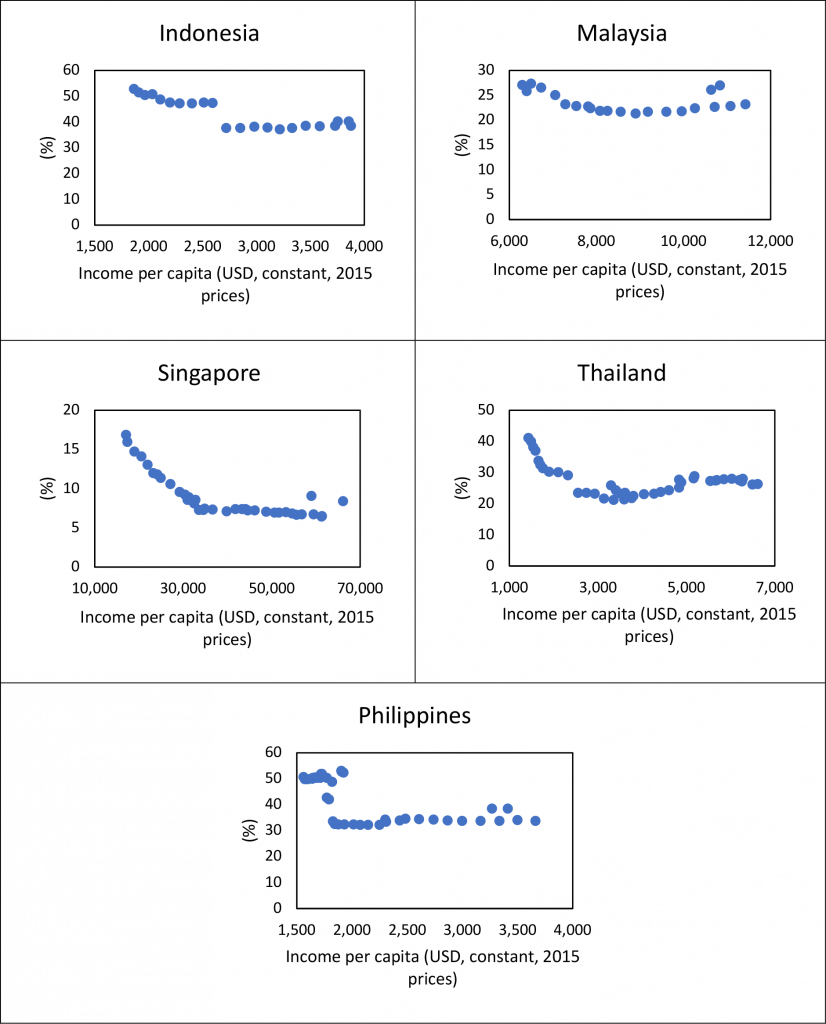

Commonly, a relative decline of the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP raises the spectre of “premature deindustrialisation”. This term highlights decline in the manufacturing sector’s contribution to the economy happening before the country has become fully developed (or attained a high level of GDP per capita). Three countries in the region have exhibited signs of premature deindustrialisation, i.e., Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. The decline in their manufacturing sector’s share of GDP has taken place at different income per capita levels—USD2,000 for Indonesia (at constant 2015 prices), USD5,000 for Thailand, and USD6,000 for Malaysia (Figure 3). In contrast to these countries, Singapore began deindustrialising only after it achieved high-income status.3 It is also interesting to note that even after Singapore experienced deindustrialisation, it experienced a manufacturing revival when its per capita income reached USD60,000. Vietnam’s experience is also interesting—it exhibited signs of premature deindustrialisation at around per capita income of USD1,300 but managed to reverse it at USD2,000, thus, apparently averted the middle-income trap (see Ohno 2009).

Figure 3: Deindustrialisation in Southeast Asia.

Source: World Bank and CEIC.1, 2

Trade and Manufacturing Exports

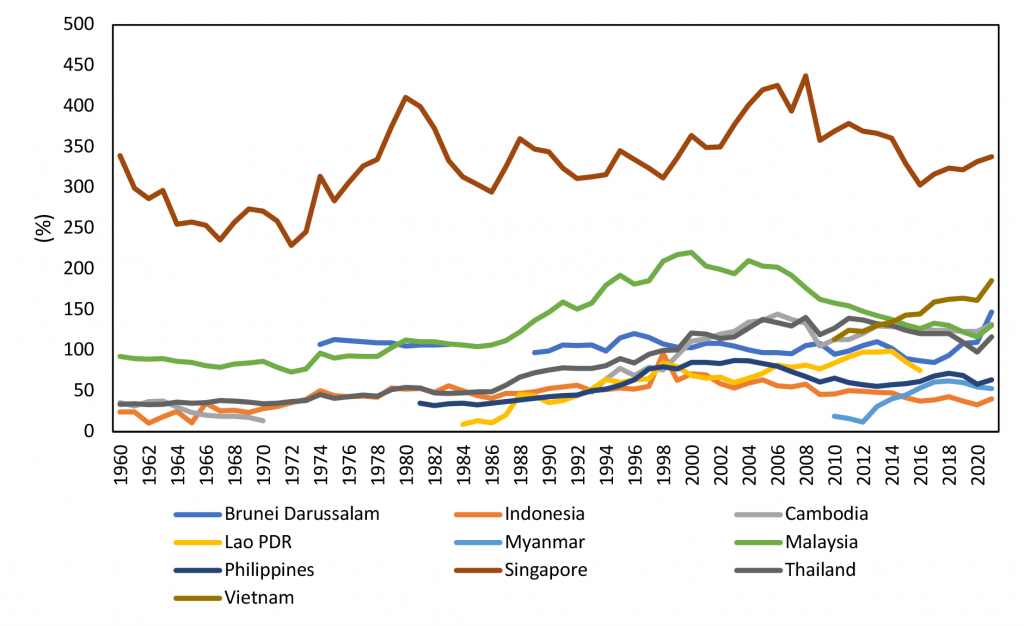

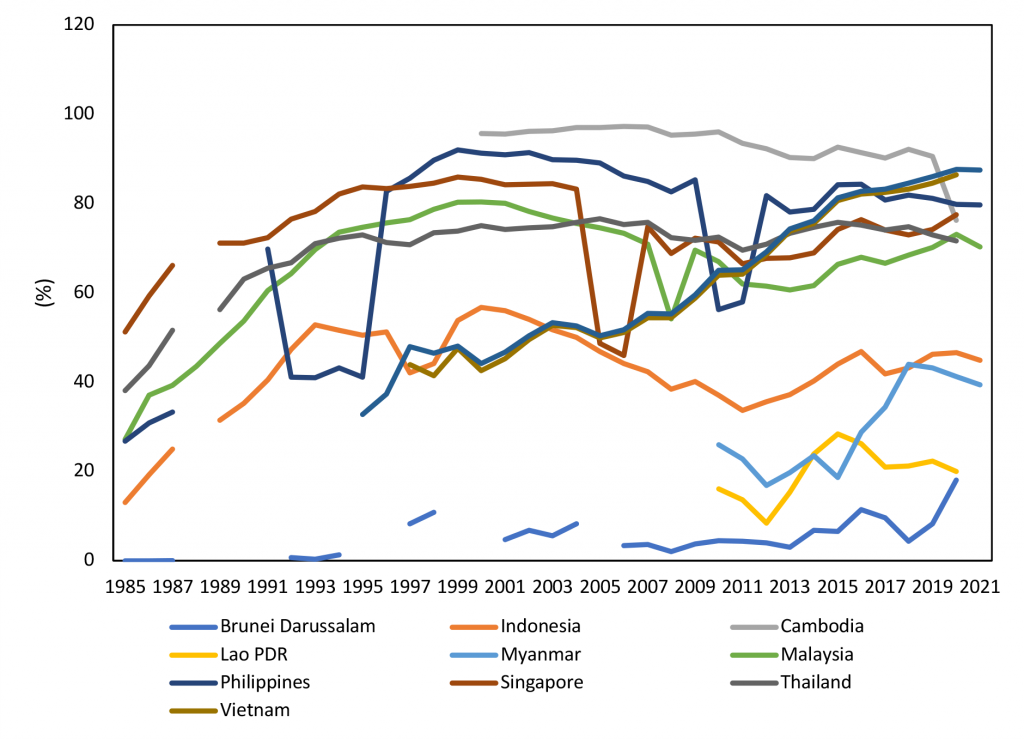

The importance of trade as driver of economic growth and structural change differs across the countries in Southeast Asia. One indicator of the importance of trade to an economy is the share of trade (exports and imports) in the GDP (Figure 4). Singapore is an outlier—it is a city state with an open economy; its trade ratio remains high despite experiencing fluctuations in the past.

Malaysia is also highly dependent on trade but the country’s trade ratio has been declining since 2000, which coincides with the commencement of its premature deindustrialisation. Clearly, the relative decline in manufacturing played a significant role. This can be seen in the decline in the share of manufactures in the country’s merchandise exports (Figure 5); however, this decline in manufactured exports appeared to have been partially reversed since 2014. The decline in Malaysia’s trade ratio is therefore explained by the decline in other exports (oil, for example).

Thailand’s trade ratio is historically lower than Malaysia’s. Be that as it may, since 2011, this has gradually declined further. Historically, Indonesia, which has a large domestic market, has relied less on trade as a driver of growth. The relative decline in its manufacturing sector has also manifested as a decline in the share of manufactures in merchandise exports between 2000 and 2011.

Amongst the CLMV countries, Vietnam has rapidly increased the role of trade as a growth driver. The country’s trade ratio has exceeded Malaysia’s trade ratio since 2014. The share of manufactures in Vietnam’s merchandise exports rose from 33% in 1995 to 87% in 2021. In Cambodia, even though the GDP share of manufacturing is relatively low, the manufactures share of exports for that country is very high. This is most likely due to the high specialisation of its manufacturing sector (in textile, which contributes 15% of GDP and 60% of total exports). In a sense, structural change in Cambodia has been constrained by its specialised manufacturing sector.

Overall, there is a clear division in development pattern between groups of countries that rely heavily on exporting manufactured goods (Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam) and those that do not (Brunei, Lao PDR, and Indonesia) (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: Trade as a share of GDP.

Source: World Bank.1

Figure 5: Manufactures exports (% of merchandise exports).

Source: World Bank.1

Consumption and Structural Change

As countries become richer, their population spends proportionately less on agricultural products (e.g., food) and more on manufactured goods as well as services. This phenomenon, associated with the Engel curve and income effects, manifests a demand-side driver of structural change. Ideally, expenditure data on three categories are needed for measuring this change i.e., agricultural goods, manufactured goods, and services. Due to general data limitations, information from household expenditures on the first category of goods are used below to illustrate this point. Furthermore, this information is available on only five countries in the region.

In the sample of countries surveyed, only Singapore—the country with the highest per capita income in the region—exhibits a clear downward sloping relationship between share of expenditures on food and per capita income (Figure 6). Upper middle-income countries such as Malaysia and Thailand do exhibit this behaviour at a lower range of their income per capita but there are some apparent reversals at higher income levels. This could imply that the demand-side factors are not conducive to further relative expenditure decline in the agriculture sector.

Both Indonesia and the Philippines have experienced decline in share of expenditure on food but in their case, these occurred in a sudden and step-wise manner. The reductions took place in the year 1999 for the Philippines while that for Indonesia occurred in 2009. One plausible explanation are the economic crises—the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998 and the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. More research is still needed to uncover the drivers behind the structural breaks in food consumption in these two countries.

Further studies are certainly needed to examine the demand-side drivers of structural change in Southeast Asia. Compared to supply-side (production) drivers, data on consumption by sectors are harder to come by. Aside from household expenditure surveys, another possible source of data could be the input-output table. Data on imported goods and services for consumption are also needed to unpack the effect of trade on demand drivers of structural change.

Figure 6: Food and non-alcoholic beverages – % of total expenditures.

Source: CEIC.2

Conclusion

Southeast Asian countries are extremely heterogeneous in terms of level of development and economic structure. Prospects for a regional convergence in per capita income have become dimmer. Countries in the region that became more developed befitted from sustained growth with structural changes that have primarily been driven by export-oriented manufacturing. But even amongst these countries, there are signs of premature deindustrialisation, especially Malaysia and Thailand. Singapore has managed to resuscitate its manufacturing sector partially at higher income levels.

For countries that have yet to achieve a significant level of industrialisation, such as Cambodia and Lao PDR, the global environment for any export-oriented development strategy that they might have has been very challenging of late—firstly, the disruptions caused by COVID-19, and secondly, the inflationary shocks worsened by the war in Ukraine. One plausible alternative open to them is to develop their services sector, especially tourism (i.e., export of services).

The research on comparative structural change in Southeast Asia is still at a nascent stage, especially when compared to the theoretical developments in this area. More studies on the demand-side of structural change in the region is needed to ascertain the region’s overall developmental prospects and patterns. For this to happen, better data need to be generated and made available for analysis.

NOTES

1 Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/ on 15 October 2022.

2 Retrieved from https://www.ceicdata.com/en on 15 October 2022.

3 In 2014, the World Bank classified high-income economies as those countries with a gross national income per capita of USD12,746 or more. See https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/10.1596/978-1-4648-0382-6_high_income_countries

REFERENCES

Chenery, H. B. and Syrquin, M. 1986. Typical patterns of transformation. In Industrialization and growth: A comparative study, eds. Chenery, H. B., Robinson, S. and Syrquin, M., 37–83. New York: Oxford University Press.

Comin, D., Laskari, D. and Mestieri, M. 2021. Structural change with long-run income and price effects. Econometrica 89 (1): 311–374. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA16317

Eberhardt, M. and Teal, F. 2013. Structural change and cross-country growth empirics. The World Bank Economic Review 27 (2): 229–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhs020

Herrendorf, B., Herrington, C. and Valentinyi, A. 2015. Sectoral technology and structural transformation. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 7 (4): 104–133. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20130041

Herrendorf, B., Rogerson, R. and Valentinyi, A. 2014. Growth and structural transformation. In Volume 2B: Handbook of economic growth, eds. Aghion, P. and Durlauf, S. N., 855–941. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Matsuyama, K. 2019. Engel’s law in the global economy: Demand-induced patterns of structural change, innovation, and trade. Econometrica 87 (2): 497–528. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA13765

Ohno, K. 2009. Avoiding the middle-income trap: Renovating industrial policy formulation in Vietnam. ASEAN Economic Bulletin 26 (1): 25–43.

Syrquin, M. 1988. Patterns of structural change. In Handbook of development economics, volume I, eds. Chenery, H. and Srinivasan, T. N., 203–273. Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4471(88)01010-1

Syrquin, M. and Chenery, H. 1989. Three decades of industrialization. The World Bank Economic Review 3 (2): 145–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/3.2.145

Uy, T., Yi, K.-M. and Zhang, J. 2013. Structural change in an open economy. Journal of Monetary Economics 60 (6): 667–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2013.06.002

About the Contributor

Cassey Lee is a Senior Fellow and Coordinator of the Regional Economic Studies Programme at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore. Prior to joining ISEAS, Lee held academic appointments at the University of Wollongong, Nottingham University Business School (Malaysia), and University of Malaya. He received his PhD (Economics) from University of California, Irvine, specialising in industrial organisation. He has published in peer-reviewed journals such as Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Computational Economics, Kyklos, Journal of Economic Surveys, and Economic Modelling. Lee is currently the co-managing editor of the Journal of Southeast Asian Economies and Associate Editor of the Journal of Economic Surveys, Asian Economic Journal, and Asian Economic Policy Review. Email: cassey_lee@iseas.edu.sg.